Life prepared writer Mac Griswold to tell the world about Shelter Island’s historical gem, Sylvester Manor, the pickled-in-time plantation founded in the 17th century and occupied until 2006 by direct descendants of the founding family and their spouses.

Her latest book, “The Manor: Three Centuries at a Slave Plantation on Long Island,” just released on July 2 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, promises to spread the word to a wider world about what historians — the few who know about it — have called the only intact slave plantation north of the Mason Dixon line.

When she was a little girl in the 1950s growing up in the rolling terrain of north central New Jersey, Mac Johnston Keith would walk the two miles to Far Hills Country Day from her home near Bernardsville and along her way see the hulking estates of the last century’s industrialists and bankers, overgrown with vines and trees poking up through what had once been gardens, landscaped knolls and tennis courts.

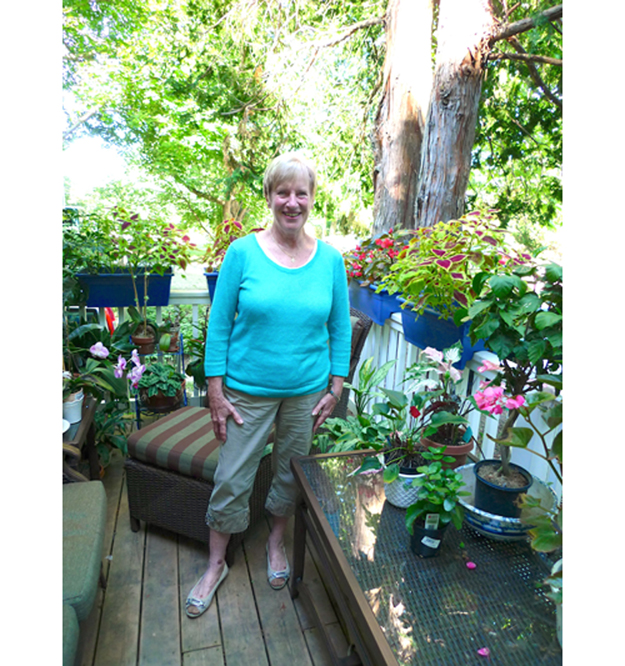

“There were all these castles and towers and some were in ruins,” Mac, 70, explained during a chat this week at Sylvester Manor. “I explored them until I went away to boarding school in Virginia at age 12.”

She knew from her story-telling father that she sprang from a Southern family that had owned a great estate, too, a place with many slaves.

Over the generations, the Keiths lost wealth and clout: by the mid-19th century, they were drifting west, where land was cheaper. By the time her father was born, the family was based in Texas. (Mac, his mother’s name, isn’t short for anything.)

Mr. Keith was determined to make up for the family’s lost fortunes and he succeeded, making a fortune in the oil business, marrying a Boston-bred runway model who would give Mac her classically refined good looks, and sending his kids to Far Hills Country Day, where Mac learned to fox hunt on horseback and, on foot, run the school’s basset hounds after hares.

A knowledge of the land, a raw nerve about slavery, a sense of wonder for history, and a fascination with old gardens and landscapes as reflections of their times and cultures would all turn Mac into a landscape historian who is now well known for her books.

They include the landmark “Washington’s Garden at Mount Vernon: Landscape of the Inner Man,” as well as “Pleasure of the Garden: Images from the Metropolitan Museum of Art” and “Golden Age of American Gardens: Proud Owners, Private Estates.”

In the newest book, based on decades of research into family archives as well as evidence scattered from Boston to London, she tells the long story of the manor and its occupants, including those who labored for the Sylvester family.

She also tells how she discovered the place. Out in the Hamptons on a summer day in 1984, a friend took Mac — by then a divorcée with two daughters and the married name of Griswold, working for the Library of America — to Shelter Island, where they rowed a dinghy across Dering Harbor to Gardiner’s Creek. He wanted her to see something he knew she’d find astounding.

Coming to the head of the Creek, Mac spied boxwoods so gigantic she knew they must have been very old. “A mudbank lies ahead,” she writes in the book, “lurking under shallow water, and we get stuck, briefly. It is only when we steer into the tide channel, stirring up silty brown clouds in the water as we pole ourselves with the oars, that we first see the big yellow house. From its hip roof and its brick chimneys to its well-proportioned bulk, the house quietly acknowledges its18th-century origins. I’m in a time warp.”

Mac learned who lived there — Sylvester descendant Andrew Fiske and his wife Alice — and wrote, asking for a chance to meet them. She became friends with both and worked with Alice, after Andrew died, to start the Sylvester Manor Project, an effort to document the estate and preserve its archives, under the auspices of the Shelter Island Historical Society. Through the process of having the ancient gardens surveyed to illustrate an article Mac was writing for the New England Journal of Garden History, she made connections to an archeologist at the University of Massachusetts, to which Alice eventually would give $650,000 to found its Andrew Fisk Memorial Center for Archeology.

About that time, Mac was working on her book about Washington’s Mount Vernon gardens. “That’s when I first got the picture of how slavery and the gardens were interconnected,” she said. “Every time Washington said ‘I did this,’ he meant the 300 people working for him did it.”

“That made me think of my visit to the manor in 1984,” she said, after the Fiskes had invited her over. “I was in the front parlor and I asked Andy where that door led and he said, ‘It goes to the slaves’ quarters.”

One of several differences between a Southern plantation and a Northern one, she said, was that slaves didn’t live in cabins on the grounds but up on the third floor, in the attic, as they did at Sylvester Manor.

She began her research for the book in earnest in 1997. In addition to poring through the vast Sylvester Manor family archives, most of which have been donated to New York University, the rest to the Shelter Island Historical Society, she traveled to Amsterdam, where manor founder Nathanial Sylvester lived for a time, to Africa to better understand the history of slavery and to Plimouth Plantation in Massachusetts, where researchers on English dialects were able to tell her how Nathaniel Sylvester talked. Mac, who bought a home in Sag Harbor in 1972, recently sold her house and moved to East Hampton. She has “Irish twin” daughters, (born a year apart) one a clinical therapist in Seattle and the other, who lives in Boulder, a media lawyer specializing in the environment.

She’s been making her living as a writer ever since the early 1980s, when she sold a piece to the New York Times magazine about a man in Harlem who made a garden out of rocks.

“I was stupid enough to quit my job” with the Library of America, the small nonprofit founded by Random House Editor Jason Epstein that republishes the works of great American writers. She did promotion, some production work and wrote the flap copy for the covers.

Somehow, she recalled, she had to come up with the right things to say in very few words and meet the approval of an advisory board of academics. When a grumpy Epstein one day complimented her work, she realized something: “It had never occurred to me I was a writer.”

She had studied English and history at McGill University and then went to New York and worked at various jobs, including sitting in a basement applying gold leaf to objects in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

She married investment banker Benjamin Griswold in 1967. They lived near Baltimore, where Mac raised her daughters. After an amicable separation, she moved with her two daughters and two dogs to New York in 1979, where she landed that job with the Library of America, where she worked for four years.

During that time, she commuted to Cambridge to attend a garden history program at Radcliffe; she later continued her landscape studies at the New York Botanical Garden’s horticultural division.

Writing magazine articles for a host of publications, from the Times magazine to Travel & Leisure, she pitched her first book idea featuring the gardens at the Metropolitan Museum, which she had come to admire but which, she realized, patrons largely took for granted.

Mac is now represented by the prestigious Andrew Wylie Agency. She had a contract for the manor book with Houghton, Mifflin, which wanted to call it “Slaves in the Attic,” but when the company changed hands she lost her editor there and a new editor wanted a book that focused exclusively on the manor’s 17th-century history.

It didn’t take any arm-twisting for her close friend Jonathan Galassi, the president of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, to pick up the book. He was familiar with Sylvester Manor — he’d been there and knew Alice Fiske, Mac said — and let Mac write it as the more intimate and expansive history she wanted.

A proposal for her next book is in the works. “It has a couple of working titles,” she said, “but we’ll go with this one: ‘The Other Paradise: Gay Men and Their Gardens.’ It will explore the unspoken “elephant in the room,” she said, about how gay men lead domestic lives that are more beautifully articulated.”